The Sport That Broke Me

Not all childhood sport activities create champions. Some just create trauma.

Today, I write about something I have held inside for 25 years. This is not a pleasant story, nor an easy one to share. But it is mine (and trust me, I wish it wasn't). It confirms that my publication is about life first, niche second.

I stand by the wooden wall bars, swinging my leg as high as I can. I am forced to keep up with the fast rhythm of my coach’s counting. Over and over. Higher. Faster. No slowing down.

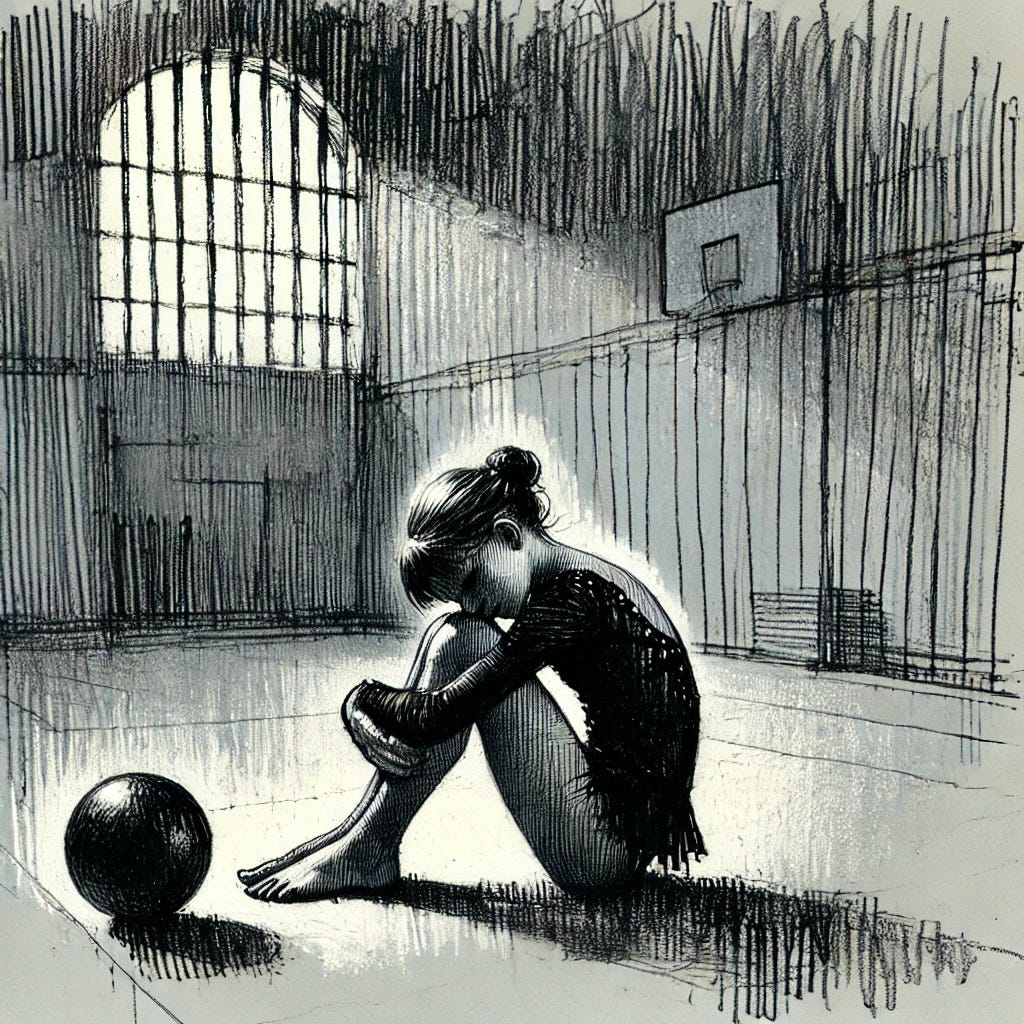

I stare out through the barred window. It’s already getting darker outside. I have learned to guess how much time is left—maybe around five o’clock. Two more hours out of four left. I imagine that outside, the world is moving without me—people walking, birds flying, dogs running freely. They can go wherever they want. I can’t. I am trapped in this gym. Then—a rough grip on my leg.

Before I even understand what’s happening, my coach yanks my foot up and slams it against the wooden bar behind me.

"Too low," she hisses, half in Russian. "Your flexibility is terrible."

Then—a pull at my bun, upward. Hard.

"This is how you stretch. This is how you stand tall."

She mumbles something about my messy bun—how it’s already coming apart. As if it’s my fault she just ripped half of it out.

Rhythmic gymnastics is a sport that blends athleticism with performance. It demands extreme flexibility, strength, coordination, and control, all while maintaining an illusion of grace and effortlessness. Gymnasts use five types of apparatus—rope, ball, hoop, clubs, and ribbon—each requiring precise mastery. To the outside world, it looks like dance, like beauty in motion. But behind the performances lies something entirely different.

I never dreamed of being a gymnast. I didn’t even know what it was. I was six years old when, by pure coincidence, I ended up at an open recruitment event. A friend of my grandmother knew about it, and someone suggested I should go. I had no expectations—I was just a child, running around a gymnasium with dozens of other little girls, unaware that this day would shape the next several years of my life.

Then, I was chosen. The trainer saw something in me. I had no idea why or what it meant. I didn’t understand that being chosen was not a privilege but a sentence.

From that moment on, I was no longer just a little girl. I was a gymnast.

Every single day, before training, I felt fear. Not just nervousness or discomfort—real fear. I would wake up and already start thinking about it. By noon, my hands were shaking as I tied my bun, and my classmates were worried about me. After school, I rushed to catch the tram, arriving as soon as possible, only to feel miserable in the place where everything terrified me.

The fear came from one person.

My trainer was Russian, a woman who had left her country to bring her methods to ours. She was not one of the elite coaches from Russia’s national team—she was second-tier, the kind that didn’t quite make it in their own system but could still dominate in a country where the sport was not as developed. She had the knowledge, the experience, and most importantly, she had power over us.

She was brutal.

Every day, I looked out the window of the training building, ready half an hour before the start, hoping she wouldn’t come. When I saw her moving toward the building, I felt a wave of fear and sadness. I never knew what to expect. Even though the physical exhaustion from training was extreme, I cared more about her mood, as it determined everything. If she was in a bad mood, the entire training would be a nightmare. If she was in a good mood, it only meant that it would be slightly less horrible.

She believed in one thing—that a gymnast must be built, no matter the cost. Pain was just part of the process. Fear was a tool. And I, the little girl standing before her, was raw material to be shaped.

She reminded me of that every single day.

She spoke to me in the most demeaning way, tearing apart everything about me—my skills, my expression, my body, my family, even the way I spoke and looked at her. I was nothing more than something she needed to fix.

Is it possible that I performed well simply because I was the most scared one in the gym?

No matter what I did, it was never enough. I was never strong enough, never flexible enough, never straight enough. Every movement, every routine, every position had to be perfect—and perfection was decided by her alone. If my flexibility wasn’t good enough, she would force my body into position. If I made a mistake, she would physically punish me and made me repeat the routine over and over again. If I cried, she would humiliate me and tell me that if I had the energy for crying, I wasn’t tired enough yet.

I was hit, slapped, roughly touched, and had apparatus thrown at me. She didn’t just correct me—she hurt me on purpose. She wanted me to be afraid because she believed that fear would make me better. And I was afraid. Every day.

But the worst part wasn’t even the pain.

The emotional weight of it all was heavier than the physical exhaustion. The fact that the mental strain far outweighed the physical difficulty only shows how deeply I suffered.

I wasn’t allowed to stop, I wasn’t allowed to slow down, and I certainly wasn’t allowed to complain.

And if someone thinks that intense training is necessary for every athlete, I wasn’t even allowed to go to the bathroom freely, let alone drink water. The fact that during our five-hour-long weekend training sessions, the idea of eating was not even considered is yet another sign of how dehumanizing this environment was. There was no such thing as recovery—only relentless training that was destroying both my body and my mind.

And I must not forget the constant remarks about my fatness and my big stomach. Apparently, I was eating too much, and I was told that I should tie my stomach down to make it look flatter.

There was a period when we had to step on a scale before entering the gym. I remember that when I was around 10 to 12 years old, I weighed between 28 to 32 kilos (62 to 70 lbs). If, after training, I didn’t weigh less than when I arrived, I was forced to run until I lost weight.

I trained every day for four hours or more. One day, twice a day. On weekends, five or more hours.

There was no excuse for missing training. Not even illness. I could be sick, feverish, exhausted—it didn’t matter. Skipping training meant consequences.

This wasn’t just a sport. It was survival.

I was a child, and yet, I never thought about quitting. Not because I wanted to stay, but because quitting wasn’t something I believed I could do. I had been conditioned to accept this as my life. This was my world, and I had no choice but to endure it.

I stand in front of the gymnastics floor at a competition. In my hand, I hold my jump rope. I feel uncomfortable in my tight, narrow leotard, the one with the elastic band sewn into the waist—stitched directly onto my skin while I stood still, afraid to move. It digs into my waist now, holding my body in a way that is meant to make me look thinner.

But none of that matters now. The only thing I feel is fear.

I am about to compete—to prove what I have trained for, to show that I can execute difficult throws and movements, on time, to the music, with a smile on my face, flawlessly, in under two minutes.

I don’t see the edges of the carpet. I don’t see the judges’ faces. I am short-sighted, but gymnasts don’t wear glasses. And little girls don’t wear contacts.

I can’t see them, but I feel them watching.

I am terrified of my coach’s judgment if I make a mistake. Since I’m going first, I already know the score will be unfair. It always is.

I don’t want to be here. I want to disappear. But I can’t.

Then, my name is called.

I step onto the floor and begin. The same routine I have repeated a million times. My body moves on instinct, fear doesn’t stop the movements. But—the knot in my jump rope slips.

Catastrophe.

I lose the music. The floor is slick, it feels different, nothing is right. Everything is slow, unreal, like a dream.

The panic sets in. I’m off the music. I already know what that means. I already know what my trainer will say.

But I finish. I switch my jump rope for the hoop. I have no time to process what just happened. I have another routine to perform.

Rhythmic gymnastics looks elegant from the outside—girls in sparkling leotards, moving in perfect synchronization with the music, throwing and catching apparatus with precision. It is meant to look effortless, graceful, almost weightless. But nothing about it is effortless.

To make young girls appear this way, their bodies must be pushed beyond natural limits. Flexibility is not just trained—it is forced, often through extreme stretching methods that cause immense pain. Strength must be built, but not in a way that would add muscle mass, because gymnasts must remain thin, fragile-looking, almost doll-like. Perfection is expected, but perfection is never enough.

Success in this sport comes at the cost of total physical and psychological submission.

Rhythmic gymnastics is an exclusively female sport. The training environment is shaped by women coaching other women, yet instead of support, what prevails is rivalry, control, and cruelty. There was no solidarity, no kindness, no space for weakness.

Trainers used fear, punishment, and humiliation as their primary tools. Competitions were not just about skill—they were political battles between coaches, judges, and clubs. Scores were rarely based only on performance. The ranking of a gymnast was often predetermined by which coach she belonged to, and which club she represented.

My country was never among the top nations in rhythmic gymnastics. We did not produce champions, and we were never going to. The level of training, facilities, and funding could never compare to what existed in Russia or other powerhouse nations.

And yet, we trained as if we were preparing for the Olympics. The suffering, the abuse, the sacrifice—it was all for nothing. No career, no future, no reward. The competitions we attended were small, and even those were rigged and biased. There was no real recognition, no prestige.

So what was it all for?

For the pride of the coaches. For the power of the judges. For the illusion of success.

For the broken little girls left behind.

Does anyone truly believe that this is how little girls should live? That they should endure all of this just to look beautiful in competition leotards? Was this even a sport?

I often compare my experience to that of people who survived concentration camps.

I see nothing good in it. Training in rhythmic gymnastics gave me nothing. It only took from me—so much that I still haven’t healed. Some may say it taught me discipline—but I was already disciplined at home and in school. Some may say it gave me a nice posture and body—but that was in my genes. Some may say I gained success—but my medals are not with me in my home.

It gave me horrible trauma.

I feel sadness.

No child deserves to suffer like this. And certainly not for the sake of a sport, for playing an instrument, or for any other activity that should help them evolve in any way. Places like the one I trained in should not exist. It does not matter what a gymnast can achieve—this is not the way to learn. No success is worth breaking a body and a soul.

Sorry there is no positive reflection for the ending.

Wow. Lots in here that sound similar to my experiences being in dance, specifically ballet, as a child at a rigorous dance studio. I've thought recently about writing about my own experiences regarding that but doubt I could the story justice the way you did so beaufully here with your own.

I found your link through the article #79 on Play Makes Us Human. I'm so sorry you went through this! Before resigning after this season, I coached track and field for 12 years...and my goal was to give kids a positive experience no matter their skill level. What you experienced was terrible/abusive and I hate it...and I know you aren't alone in having bad (and worse!) experiences. It makes me angry and so sad.